#NOISE12: Remembering Rob Gretton

Of mods in brogues, a Union Jack cape, the Kippax and the kibbutz .. of Benchill, Baguley and the wild dogs of Wythenshawe..

Rob Gretton was born on January 15th, 1953, nine days before me.

We were friends from the age of 11, toerags from the sprawling Wythenshawe estate who passed the Eleven Plus exam and attended the posh Grammar School. Even though we grew up less than a mile from each other, Rob in Baguley, me in Benchill, we hadn’t met until we started at St Bede’s.

By the age of 15, with a shared love of Manchester City and soul music, we were young mods sporting "French crewcuts," Levi's jacket, Levi’s Sta-Prest or Wrangler Evvaprest trousers and shiny brown brogues, sneaking into the Firbank pub on a Friday night before catching a live band at St.Peter's youth club. Our favorites were The Exits, a band of kids from Moss Side who played covers of the Stax and Motown tracks we adored. After the pub closed, we occasionally hitch-hiked through the night together to watch City play in exotic far-away places like Coventry, 100 miles down the M6 motorway. (Now, as a father of twin sons, I still can’t quite believe how cavalier we were allowed to be.) Rob was even more adventurous than me in that respect – when he was 16 he hitchhiked all the way to Bilbaoa in Northern Spain to watch City! The local paper - I can’t remember if it was the Manchester Evening News or its weekly soccer special, The Football Pink - ran a news story, complete with a photo of him at the stadium. We peers were suitably impressed.

Both obsessed with music, I occasionally persuaded him to “wag” school with me and attend a lunchtime recording of the BBC’s Radio One Club at The New Century Hall. We’d blag tickets to tapings of the pop show "Discotheque" at Granada TV studios. It’s a pity those tapes were never archived as I can still remember how chuffed we were to see ourselves in close-up on the telly. I’d love to be able to view that footage again.

By our early twenties, we were both restless, bored with the day jobs we found ourselves in: Rob in an insurance agency, me in the art and copywriting department of GUS, the mail order catalogue giant. Rob, being the good lapsed catholic lad he was, took off for Israel with his girlfriend, Lesley, where they lived and worked on a kibbutz for a few months. Meanwhile, I had started to make my first inroads in to comics and illustration and was freelancing for publications such as the girls’ comic “Romeo.”

Music was still a joint passion. I sang, played guitar a bit and could knock out a few chords on a piano, and I was alway messing around writing songs and trying to get bands off the ground. Rob didn’t display any actual musical talent, other than bellowing out chants on the Kippax Street terrace at City’s home games. But music would soon change the direction of our lives.

It’s said that the most important gigs in Manchester music history are the two that The Sex Pistols played at The Lesser Free Trade Hall in the summer of 1976. The support bands were The Buzzcocks and Slaughter and The Dogs. The audiences were sparse, but among those who attended and would go on to carve out careers in music were three of the lads who would form Joy Division, Billy Duffy of The Cult, Morrissey, Martin Fry of ABC, Mick Hucknall of Simply Red and Mark E. Smith of The Fall. Paul Morley would become one of the UKs top music journalists, Kevin Cummins is now one of the most celebrated photographers in rock history and Martin Hannett became a fabled record producer. Sometimes it seems that everyone of a certain age with any subsequent connection to music claims to have attended. Rob and I, on the other hand, were nowhere near. A gang of our friends used to head to Corfu every summer, so he and Lesley were in a tent in Kontakali for the duration. I was in Fairfield, California for a few weeks, a council estate lad loving every minute of Golden State culture shock.

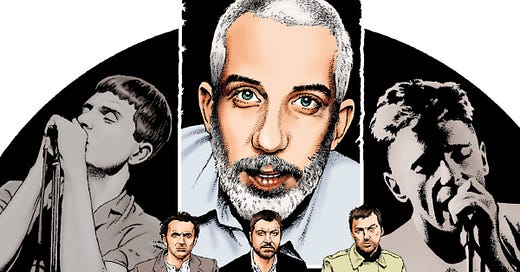

The revolution had started in our absence, but Rob was excited and enthused by the punk movement that was about to blow the doors off the music business. He latched on to local band Slaughter & The Dogs, traveling with them to gigs, helping hump the gear in and out of venues, chipping in for gas. He appointed himself fan club secretary and got me to design the band's logo and fanzine.

When he began to promote shows at The Oaks, I designed his flyers. When he started deejaying at Rafters, I was the venue's poster designer, so we'd see each other in there a few nights each week. I remember that Rob played a lot of bluebeat in among the punk and new wave. In my mind's eye, I can still see Gary Holton and members of his band, Heavy Metal Kids, bouncing around the bar at Rafter's as Rob played Dillinger's "Cocaine In My Brain." To this day, if I hear Junior Murvin's "Police and Thieves," I'm back in Rafters with Rob. Mine was a lager, his was a Pernod and black.

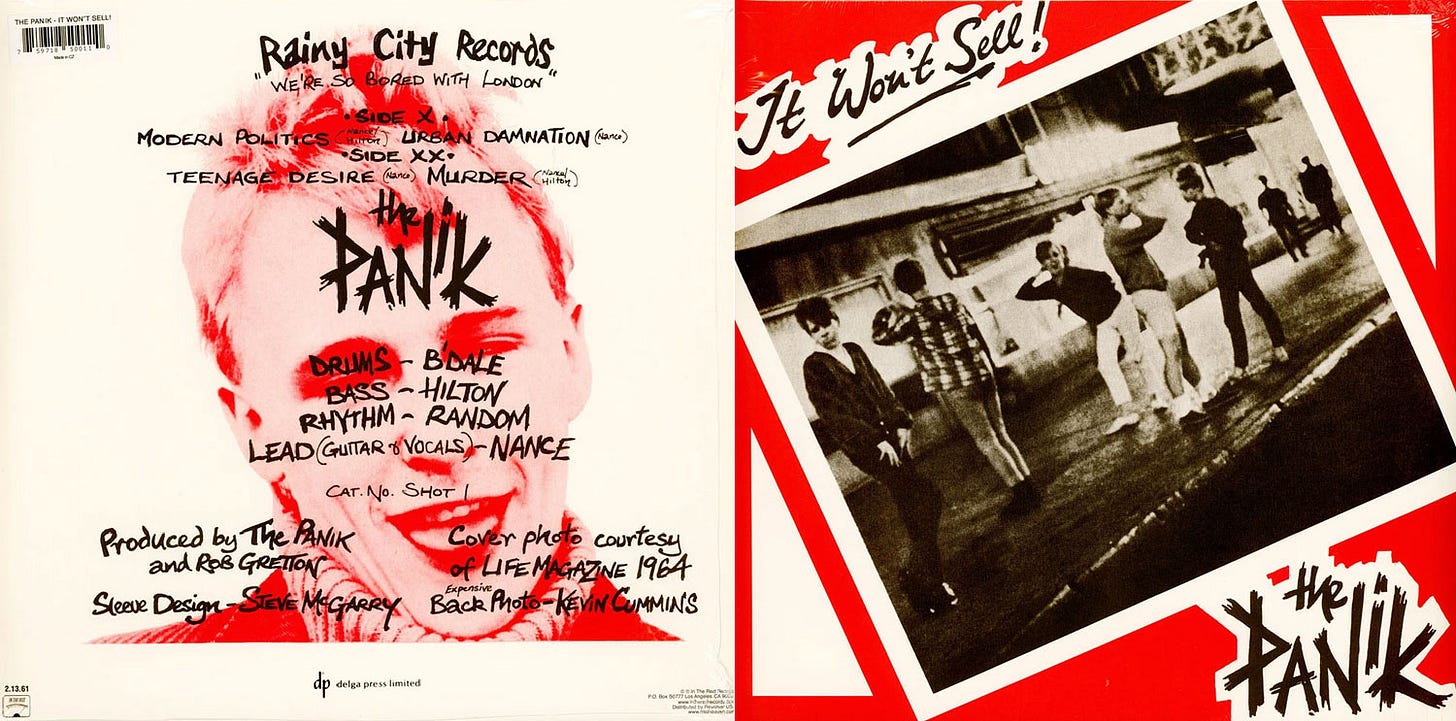

When he put out a single for The Panik, the first band he managed, he got me to design the sleeve. He was working part-time for the council as a census taker at the time, and I remember that he was chased though the streets of Benchill by a pack of wild dogs when he called round at my Gran's house to pick up the artwork.

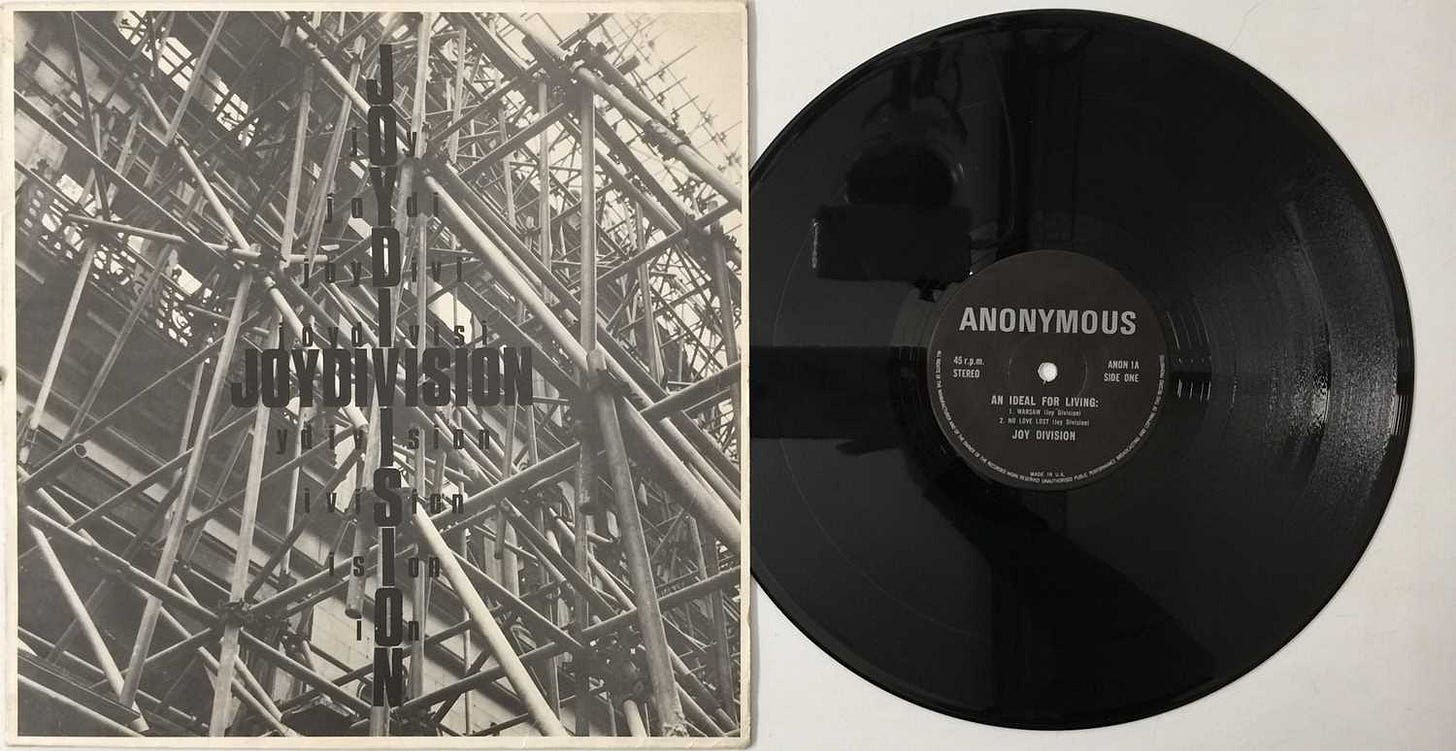

A few months later, he'd started managing a fledgling outfit called Joy Division, and he got me to design the sleeve for their first 12” E.P. That sleeve, designed on my Gran’s kitchen table in that little two-up-two-down council house, would one day go on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Gradually our paths drifted apart, me getting more involved with newspapers and magazines, Rob becoming a music mogul! We stayed in touch over the years - he and Lesley danced at our wedding, he took me carousing in the Haçienda, I took him onto the Daily Star’s editorial floor in the old “black Lubianka” building in Ancoats. He stayed with us in L.A. after I'd moved out to California with my wife and kids and we'd occasionally meet up when the McGarrys were back in Manchester, though not as much as I now wish we had.

Rob died in 1999, at the age of 46. He had achieved incredible things in life - steering Joy Division and then New Order to huge success, co-founding Factory Records and The Haçienda, launching the label that discovered Doves. In death, he was eulogized and lionized.

But when I think of Rob, I’m remembering the 15-year-old who, having had his front teeth extracted, refused to talk or smoke at a house party we all attended … until the lights went out so kids could make out in the darkness. I can still hear him exploding into joyful whoops and bellows amid our laughter.

In City’s first-ever European Cup fixture in 1968, they hosted Turkish team Fenerbahçe at the old Maine Road ground. At the final whistle, Rob and I made our way from the Kippax Street terraces, through the Platt Lane end, and around to the main stand. The pitchside gate was open and we brazenly raced onto the track. Either side of the team’s entrance tunnel were the coaching staff dugouts and we leapt on top of one each, determined to roar our support for City to the few dozen Turkish supporters who had made the pilgrimage. Rob was draped in his usual match attire, a Union Jack with MANCHESTER CITY emblazoned on it, tied around his shoulders like a cape. I was banging a tambourine that I used to take along to games to enhance the chanting. The crowd was busy shuffling towards the exits so I think the only people who paid any heed to an ardent pair of idiot 15-year-olds were the two policeman who wearily told us to get down and escorted us out of the stadium. A hugely embarrassing episode when I think of it now, but at the time we felt like genuine bad boy outlaws.

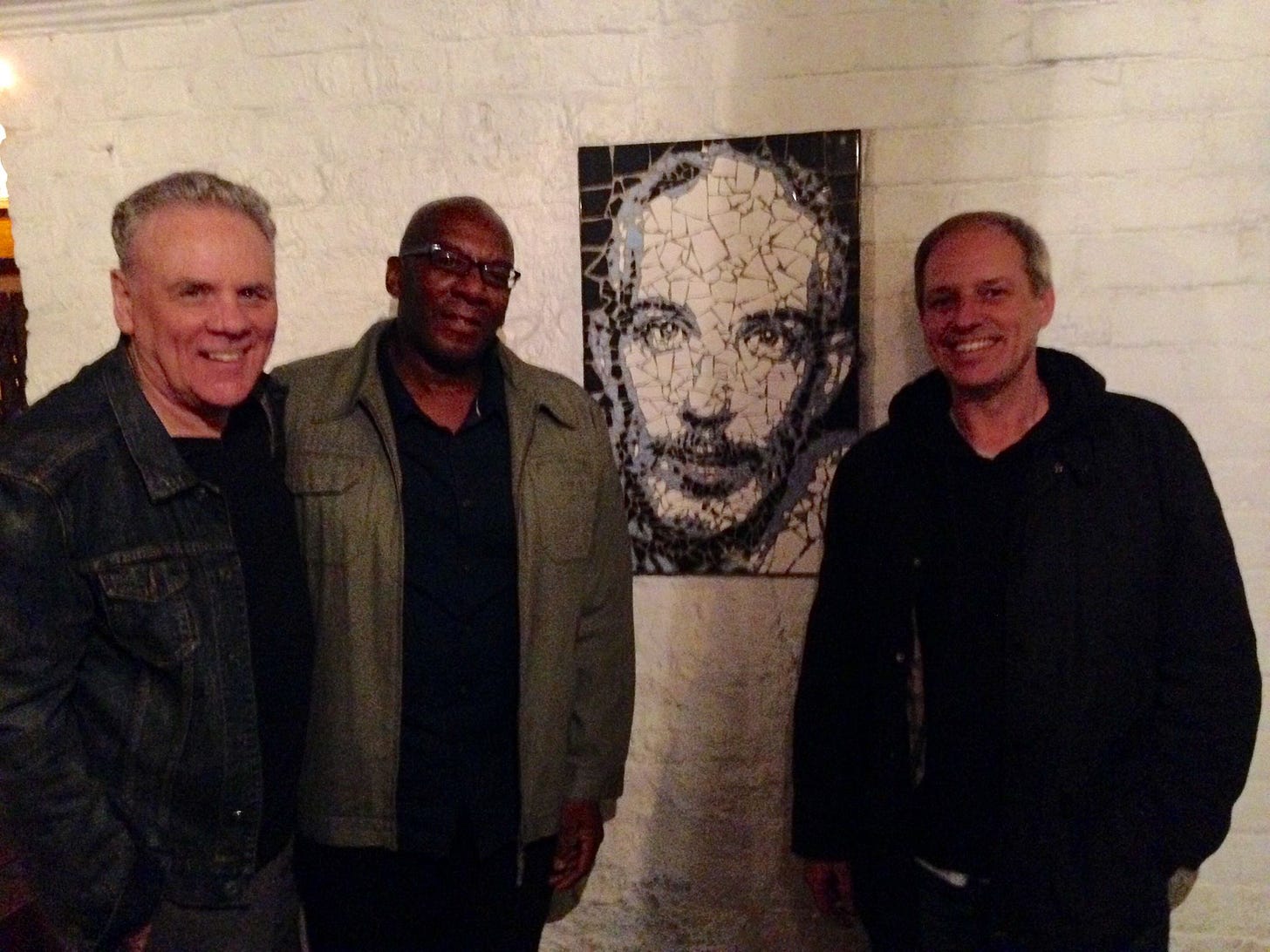

Whenever I’m back in Manchester, I invariably end up in The Briton’s Protection pub, which was Rob’s watering hole around the corner from The Haçienda, having a drink with Donald Johnson and Dave Rofe. There’s a mosaic homage to Rob hanging in the patio at the back of the pub.

Donald, the drummer with A Certain Ratio, has been one of my closest pals for nearly 50 years now. Dave manages Doves and got his start in the music business working in Rob’s office. The conversation invariably turns to our departed mate and we swap stories of a lad that was loyal, warm, generous, but hard as nails if he had to be … or if he just felt like it … and funny, in that dry, laconic Gretton way.

I remember one time in California when we talked long into the night about family we’d lost and illness and kids and all the other things that grown-ups do … but those are private moments. Instead, here’s a video where Rob delights in telling me all the people that didn’t like me:

There’s an anecdote that speaks to the affection in which he is held by those who knew him well. In 2012, when City won the League title for the first time in 44 years, fellow City fan Kevin Cummins emailed me a pic of Rob’s grave, headstone draped in a City scarf, adorned with a newspaper sporting a banner headline about the City triumph Rob would have loved. My first thought was to send it along to Dave Rofe, another true Blue. A few minutes later, he replied. It was Dave who had actually put the items on Rob’s resting place, taken the pic and sent it to our pal Kevin.

Yes, there’s quite a few of us who were fond of Rob.

I previously wrote at length about how Rob was instrumental in kickstarting my career in this piece about my involvement with Rabid Records and the work I did for Jilted John:

#NOISE002: How I framed Jilted John ... and messed up his mice!

“I was so upset that I cried all the way to the chip shop …”

Wonderful

Brilliant piece. I had the pleasure of having a few pints on a couple of occasions with Rob in ‘the vault’ of The Beech in Chorlton. We had mutual friends. We just talked City, nothing else. What a top bloke. P1ss funny, too.

46 is no age is it?

...sake… :-(